“The happiness gap: how happy days are here again – but not for all”, “Women no longer the happier sex” or “Money really does buy you happiness, study reveals” – these are just three of the typical headlines that have accompanied releases of personal well-being data over the last five years. But why are we collecting statistics on personal well-being and how can they be used to inform decisions which affect daily life in the UK?

In the past, measuring the UK’s progress had largely been assessed in economic terms, for example on the basis of measures such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per head. However, these traditional measures are increasingly considered as providing an incomplete picture of the state of the nation.

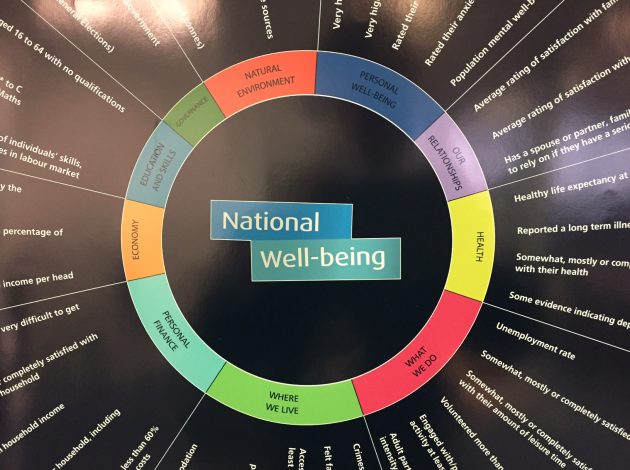

Our strategy for ONS is “better statistics, better decisions” and we are constantly looking for ways in which statistical data can add value to policies that affect everyone. This need for a richer picture of how we are doing as a nation led to the Measuring National Well-being Programme in 2010 and this is where personal well-being comes in.

“This kind of information can shed a whole new light on how people feel about their lives, regardless of the national economic picture.”

Each year since 2011, about 160,000 of us across the UK are asked personal well-being questions, allowing people to make an assessment of their lives overall, as well as providing an indication of their day-to-day emotions. The questions go beyond asking people about their happiness. We also ask about anxiety levels, how satisfied people feel with their lives overall, and to what extent they feel that the things they do in life are worthwhile. This kind of information can shed a whole new light on how people feel about their lives, regardless of the national economic picture.

In Northern Ireland, for example, we continually see that despite often performing less well economically than other parts of the UK, they continually report the highest well-being across all four measures. This perhaps demonstrates what Robert Kennedy said as long ago as 1968: “Gross National Product… measures, in short, everything except what makes life worthwhile”.

Personal well-being statistics can help policymakers to target their initiatives where they will make the most difference to the quality of people’s lives. For example, our release in February 2016 looked at personal well-being over the life course and found two important things.

Firstly, that the lowest well-being across all four measures is seen for those in their middle years. This might in part result from the dual burden of balancing caring responsibilities alongside work pressures.

Secondly, that well-being is highest for those aged between 65 and 74, after which it falls. The largest decline is seen for feelings that things done in life are worthwhile. This could potentially be reflecting barriers to services for the older age groups and presents a challenge which will only become greater in an ever-ageing population.

Furthermore, recent research from the What Works Centre for Well-being, using the four ONS well-being questions, has shed light on the EU referendum result. They found that areas with high levels of well-being inequality were more likely to vote to leave, whereas areas with lower levels of well-being inequality were more likely to vote to remain. In the same study income inequality was not shown to impact voting preferences.

Next week we are publishing our latest personal well-being findings for the year ending September 2016, presenting for the first time annual estimates on a rolling quarterly basis.

There is an old adage that ‘what gets measured gets done’. Well-being data is giving policy makers additional insight and information that can help to improve the lives of people in new ways, ways that will perhaps mean as much or more to them as the country’s economic progress.

Glenn Everett is Director of Well-being, Inequalities, Sustainability and Environment at ONS