Ten big questions about the UK’s migration figures

By Jay Lindop

How does ONS measure migration into the UK?

The International Passenger Survey (IPS) estimates migration flows – that is people entering and leaving the UK by interviewing a sample of passengers travelling through the main entry and exit points from the UK including airports, seaports and the Channel Tunnel.

Is the International Passenger Survey reliable?

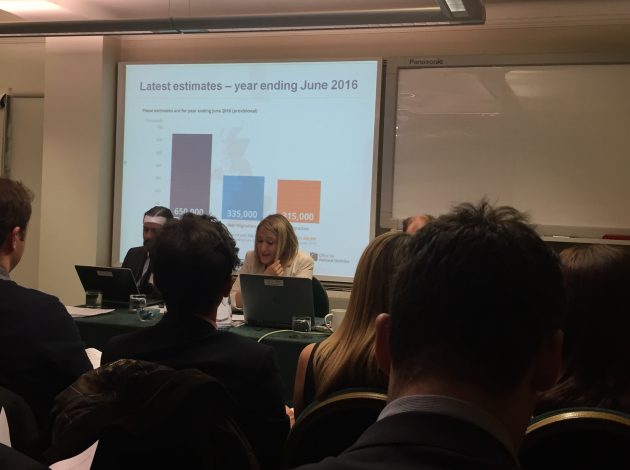

The IPS provides a reliable overall estimate of net migration – the balance between immigration and emigration – into the UK as a whole and this is used to inform policy and political debate. As a sample survey, however, there is a degree of uncertainty around these estimates. So when it publishes the migration figures ONS also makes it clear how much the actual picture might differ from the estimates so everyone can understand the quality of the data they are seeing.

More detailed figures- for example on the number of students coming into the UK – have higher levels of uncertainty reflecting the fact that they are based on smaller sample sizes but these levels of uncertainty are all published too

What is ONS doing to improve its migration statistics and the impact of migration?

While the IPS provides robust information on those coming into and leaving the UK there is less information to answer some of the big policy questions relating to those migrants resident in the UK. How are public services affected by migration? Or how much do migrants contribute to the economy, nationally and locally?

Earlier this year, we started work to identify how sharing, linking and exploiting other sources of data – some of it already held by other government bodies – could help us to produce more detailed analysis of the impact of international migration on the economy and public services.

We also plan to explore how many non-EU students depart the UK by the time their visa expires and how many remain in the UK after completing their study.

Why do you include students in the net migration figures?

We use the United Nations definition to make sure our figures are internationally comparable. The UN definition of a migrant is someone who changes their country of residence for a period of one year or more. As many educational courses last longer than a year, that definition obviously includes many students. Net migration figures are used by ONS to calculate the size of the UK population in any given year and they include international students since they contribute to population growth. These population figures are used by national and local government to inform their planning and removing any key group would have consequences for this.

How many students leave the UK when they complete their studies?

The International Passenger Survey (IPS) is the only currently available data source that identifies those emigrants who originally immigrated to study in the UK. We have investigated how the IPS is identifying students in more detail, including whether students’ actual migration patterns follow their original intentions, as this has been the focus of considerable interest this year. Latest figures show that of those emigrating, 66,000 originally came to the UK to study in the year ending March 2016.

There are reasons why this figure is lower than those currently migrating to the UK to study including:

- Students staying longer than initially expected and obtaining extensions of stay in the UK, whether as a student or in other categories such as skilled work;

- Students finishing their courses and overstaying their visas;

- The IPS not completely recording student flows, either due to sampling or non-sampling errors (such as not responding to the survey or responding incorrectly); this is a question of recent increasing prominence;

- When student migration is in a period of growth, as it generally has been in the UK since the 1990s, then student numbers will make a positive contribution to net migration during that period because the numbers arriving in any year will tend to be larger than the numbers leaving (reflecting the lower number of previous years’ arrivals); if student immigration were to decline, the opposite will be true.

Could ONS produce a different net migration figure that excludes international students?

The published net migration figures by reason for migration are based on the difference between the number of people immigrating for a particular reason and those emigrating for the same reason. Therefore, the published net figures by study will show how many more people immigrate for study than emigrate to study abroad. In effect, this figure will show whether or not the UK is a net importer or exporter of students. This is different from a net migration figure of the number of student immigrants minus the number of former students who have emigrated. Such a figure is not yet currently possible to produce.

It is straightforward to remove the estimated number of student immigrants from the total immigration flow in any particular year. However, there will be some students who do not emigrate when their studies have finished and these numbers will need to be added to the (non-study) immigration flow. Data sources are currently limited on what students do when they have completed their studies. The IPS measures the number of emigrants who previously arrived to study and there is visa information on the number of non-EU students who get an extension to remain in the UK. ONS plans to make better use of administrative data that will provide a fuller picture of how many students remain in the UK after their studies (e.g. for work) and how many non-EU students on study visas depart the UK. When these sources are available and are considered to be of satisfactory quality for statistical purposes, ONS could produce alternative breakdowns of the total net migration figure.

What proportion of growth in the labour market is due to foreign workers?

Employment statistics from the Labour Force Survey showed there was an increase of 454,000 in the employed UK labour force in July to September 2016, compared with the same quarter for the previous year; of this 47% can be accounted for by growth in employment for British nationals, 49% by growth in employment for EU nationals with the remaining 4% accounted for by non-EU nationals (these growth figures relate to the number of people in employment rather than the number of jobs and therefore show NET changes in the number of people in employment).

Why are short-term migrants not included in ONS’s headline statistics on international migration – they’re important too.

Short-Term International Migration estimates for England and Wales, covering those coming to the UK for 1 to 12 months and 3 to 12 months are published annually by ONS, with the most recent (for mid-2014) published in May 2016. This also shows the impact that these short-term migrants have on the population. ONS is consulting on whether or not users would find it helpful to have these statistics released more frequently.

ONS’s headline statistics on international migration are based on long term migration which are in line with United Nations definitions of a long term migrant.

When will we know whether Brexit has resulted in lower migration?

At the moment nobody knows how Brexit might limit the freedom of EU citizens to live in the UK – or vice versa. But in February 2017 we will see an indication of the immediate impact following the referendum result when we publish the annual migration figures with data for the year ending September 2016.

Where can we find more information about how ONS measures migration?

- The Migration Statistics Quarterly Report (MSQR) – a summary of the latest official long-term international migration statistics published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the Home Office and the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

- International Migration Statistics First Time User Guide – an introduction to the main concepts underpinning migration statistics including basic information on definitions, methodology, use of confidence intervals and information on the range of available statistics related to migration.

- Note on the differences between Long-Term International Migration flows derived from the International Passenger Survey, and estimates of the population obtained from the Annual Population Survey – a summary of the differences between LTIM flows estimates and the stocks data provided by the APS, highlighting why the year-on-year change in the APS should not be used as a proxy for a measure of international migration flow.

- Note on the difference between National Insurance number registrations and the estimate of long-term international migration: 2016 – in-depth research into the differences between NINos and the IPS.

- International student migration – what do the statistics tell us – information on the differences between various migration data sources. An update to this paper was published on 16 November 2016 to better understand student migration to and from the UK.

- Comparing sources of international migration statistics – a note to help users of migration data understand that the differences between the various sources are driven by differences in definitions and coverage.

- Consultation on International Migration Statistics Outputs – The purpose of this consultation is to gather insight and seek user views on the presentation and timing of the Government Statistical Service’s international migration statistics outputs and specifically what products are used, why and what other data sources users would like to see published.

Jay Lindop is Deputy Director for Population Statistics at ONS

Feedback to the Editor