Explaining trends in baby loss in England and Wales

While stillbirths continue to decline, the neonatal mortality rate has increased slightly in recent years. Gemma Quayle discusses today’s latest trends and progress against the Government’s ambition to halve stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates by 2025…

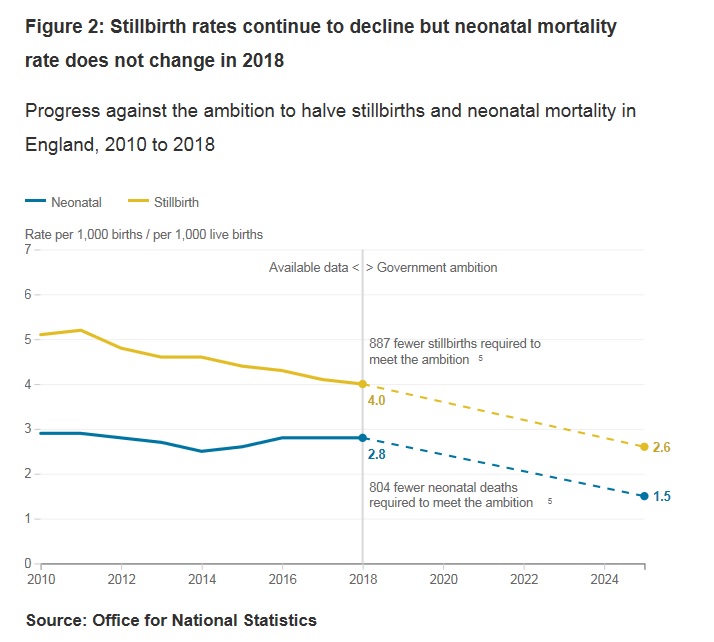

Understanding why newborn babies die is fundamental to future prevention. In 2015, the Department of Health and Social Care announced an ambition for England to halve stillbirth and neonatal mortality (deaths under 28 days) between 2010 and 2030. In 2017, this goal was brought forward five years to 2025.

Our statistics are vital for understanding how England is progressing against this ambition. Our latest analysis into specific groups helps us to investigate the trends in more detail and understand what is behind any changes in the rates.

So what’s been happening since 2010?

Stillbirth rates in England have been declining since 1993, when it was 5.7 stillbirths per 1,000 births, and this has continued since 2010 when the rate was 5.1. Our latest data shows the rate has dropped to 4.0 in 2018. To achieve the national ambition the rate would need to fall further to 2.6 in 2025. If the number of live births remained the same, this would mean 887 fewer stillbirths compared with the 2,520 reported in 2018.

Neonatal death rates have not seen the same decline in recent years. In 2010 there were 2.9 neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births. Despite reaching an all-time low of 2.5 in 2014, the rate increased to 2.8 in 2017 where it has remained this year. To achieve the national ambition the rate would need to fall to 1.5 by 2025. If the number of live births did not change, this means 804 fewer neonatal deaths compared with the 1,742 reported in 2018.

Internationally, the UK has a relatively high neonatal mortality rate compared to other high-income and industrialised countries. Some of this variation can be explained by differences in how live births are defined between countries, but generally our rates have been falling more slowly over time.

The continued decline in stillbirths in England coupled with the rise in neonatal deaths within the same timeframe raises questions about what is driving these trends, what it means for the government ambition, and for making international comparisons.

Can we explain these trends?

Definitions are important. In the UK babies who are assessed as showing no signs of life are classified by health practitioners either as stillbirths (at 24 weeks or more completed gestation) or late fetal losses (before 24 weeks). Late fetal losses do not appear in either our births or deaths statistics, but are collected by MBRRACE-UK. Our statistics do, however, include the deaths of all live born babies regardless of their gestational age.

One explanation offered for recent increases in the neonatal mortality rate is that more pre-term babies are being classified by health practitioners as live births, particularly those born before 24 weeks completed gestation.

Since 2010, despite a fall in the overall number of births, there have been more live births at under 24 weeks gestation.

Sadly, although more babies under 24 weeks are born and assessed as showing signs of life, most only survive a short time. Two thirds of babies born with signs of life under 24 weeks die within a day of being born, and over 80% do not survive the neonatal period. These babies appear in both our birth and death statistics, but if they hadn’t been assessed as showing signs of life, they would not appear in either.

We can check the impact this has on the overall trend by looking at neonatal deaths for babies born at 24 weeks or over. For this group we do not see an increase, so the recent rise in the overall rate can clearly be accounted for by the group of babies born before 24 weeks. However, the neonatal mortality rate for babies born 24 weeks or over has levelled out since 2014 rather than continuing its previous downward trend. So whilst the increase in live births under 24 weeks is part of the picture, it is not the whole story.

Why are there more babies born alive before 24 weeks?

This is not something ONS can uncover from the data alone.

In recent years, advances in perinatal care have led to an increase in the number of babies born alive before 24 weeks. However, work is well underway to address a lack of clear guidelines for health practitioners on assessing signs of life which has led to inconsistent decisions about whether a birth is classed as a live birth or not.

MBRRACE-UK* are currently developing guidance for doctors and midwives for assessing signs of life for births under 24 weeks, where active survival-focused care may not be appropriate.

If these guidelines are introduced, and clinical practice changes, this may impact future stillbirth and neonatal death rates.

What are the next steps?

As we move closer to 2025, the insights we can offer to infant mortality statistics will become increasingly relevant to assessing progress towards reducing stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Gestational age is not the only risk to a baby’s survival. A whole range of complex risk factors relating to maternal health, deprivation and other inequalities influence infant mortality rates, and could be explored in future research.

Numbers and rates aside, we must not lose sight of the fact that every baby death is a tragedy. Sands, the stillbirths and neonatal deaths charity do important work to support bereaved families and reduce baby death. If you’d like to know more about their work or have been affected by baby loss, please visit their website (https://www.sands.org.uk/)

Gemma Quayle, Senior Research Officer, Health and Life Events Division

*MBRRACE-UK is the collaboration appointed by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) to run the national Maternal, Newborn and Infant clinical Outcome Review Programme (MNI-CORP) which continues the national programme of work conducting surveillance and investigating the causes of maternal deaths, stillbirths and infant deaths.