Productivity gap narrows

New OECD figures published today suggest the ‘productivity gap’ between the UK and other economies including France, Germany and the USA is smaller than previously thought. The latest estimates follow a re-appraisal of how each country measures the number of hours worked. Richard Heys discusses how the development of these improved numbers is in part down to work at ONS.

Productivity growth or, more importantly the lack of it, has been one of the burning economic issues since the financial crisis. Many people have speculated on this so-called ‘productivity puzzle’: why has recent productivity growth been so low? However, there is a second and more established mystery around the UK’s productivity performance and that is why British productivity has historically lagged so far behind other developed countries; particularly the USA, France and Germany. This ‘productivity gap’ has long been a matter for speculation.

A number of explanations have been suggested trying to pin the blame on either weak UK management practices, low capital investment, or poor levels of training. Here at the ONS, as part of the work we’ve put into producing more detailed productivity estimates to identify the roots of low productivity, we’ve also taken a forensic look at how these numbers are put together in the first place.

Productivity is produced very simply by dividing how much an economy produces (GDP) by the number of hours being worked. While we knew that GDP figures were compiled in very similar ways across the developed world, we thought there might be scope for different countries to produce hours worked estimates in slightly different ways, which could lead to differing productivity results.

Because these data are pulled together internationally by the OECD, before we use them to produce our own statistics, we approached them to pose this question, and they agreed this was an area worth exploring. The OECD gathered data from over 40 countries to understand how they each measured hours worked and whether there were any substantial differences in methods or data.

The results of this analysis are published by the OECD in International Productivity Gaps: Are Labour Input Measures Comparable? This research reveals some striking differences in the way different countries estimate the amount of work taking place. These differences boil down to a key question: to get the best comparison, is it better for each country to produce its best estimate from the data it has available and compare, or is it better to make every country use the same methods and compare those results.

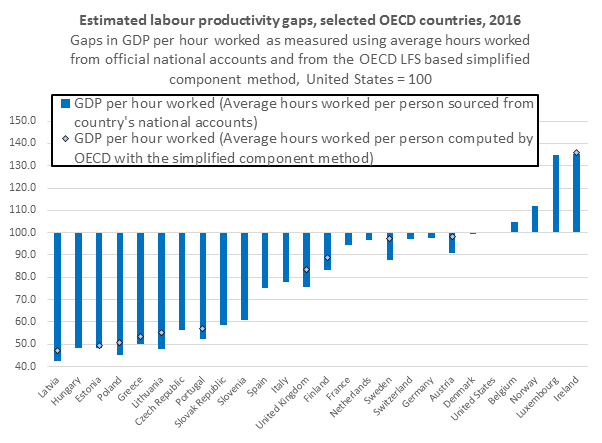

Historically each country has used the best data available to it, but the OECD’s working paper shows that, when using a more consistent method to compare total hours worked, the UK’s labour productivity improves significantly relative to other countries. For example, the UK’s productivity gap with the US would reduce by about 8 percentage points from 24% to 16% when adopting the simple component method approach.

Source: OECD (2018) International productivity gaps: Are labour input measures comparable?

Trying to align methods and data-sources across countries can be challenging. However, the ONS is now exploring how best to develop a practical method to estimate international comparisons of labour productivity on a standard approach, by using similar data-sources for each country and applying the necessary adjustments to generate estimates for other countries that are as comparable to the UK’s estimates as possible.

However, while these new results are striking, the UK’s labour productivity still lags behind many of its largest international competitors. In addition, these improved figures don’t provide any explanation for why productivity growth has been so stubbornly low since 2008. So, while this analysis significantly narrows the ‘productivity gap’, the efforts to solve the ‘productivity puzzle’ and understand the rest of the ‘gap’ will continue.

The ONS is investigating how best to implement the OECD’s proposed approach to calculate workers and hours worked estimates. In January 2019, we plan to publish an article on improving our international comparisons estimates, which will include more detailed breakdowns of how the UK compares with other developed countries on a more consistent basis.

Richard Heys is Deputy Chief Economist at the Office for National Statistics