Can social media data improve official statistics? Not yet, suggests new work on tourism

While ONS strategy is focused on making more use of government-held data to improve official statistics, researchers in the Data Science Campus are also exploring the value of social media data. There’s plenty of it and its potential seems obvious. But who is “citizen of the world” and where is “Black Pudding Land”? As well as privacy concerns some big limitations in the data need addressing too, conclude Lanthao Benedikt and Emily Tew.

Social media data is no doubt an incredibly rich data source, if only for its volume and variety. As of 2018, Facebook has 2 billion users, YouTube 1.9 billion users, Instagram 1 billion users and Twitter 336 million users. Every day, we contribute to billions of images, posts, videos, tweets etc. We post all sorts of information on these platforms, information about where we have been, where we plan to go, and even post pictures of our time at those places.

With social media being such a key part of everyday life and the data readily available online, why is ONS still conducting surveys, and how could the data revolution change the way we collect information to understand UK society. That being said, it is paramount that data sources used in the production of official statistics are accurate, relevant, unbiased, and most importantly, they must be ethical and for public good.

A mission of the Data Science Campus within ONS is to investigate data sources and data science methods that could be used to improve the way we produce statistics. We want to understand the potential and limitations of novel data sources, to what extent they could be used and what for.

In this blog, we talk about the potential and the challenges of using social media data in official statistics, using the example of tourism.

The official statistics – the International Passenger Survey (IPS)

The IPS is a well-established survey and the primary data source for official measures of tourism and migration in the UK. We have a long experience of this survey; it has been conducted by ONS since 1961. Around 800,000 face-to-face interviews are carried out every year at major seaports, airports and international train stations to collect information from tourists and migrants as they enter or leave the UK. Passengers are selected for interviews using stratified random sampling by mode of transport and time of day. The sampling frame covers 95% of international travel to and from the UK, with a response rate of between 75% and 80%. The survey is carefully designed and monitored to be in line with the quality standards defined by the European Statistical System (ESS).

However, the IPS does present some limitations, one of which is the lack of precision for small areas, as discussed in a recent article by the Social Market Foundation (SMF) on migration. This limitation can be explained by the high cost (including the burden on our survey respondents) that would incur if we were to collect a sufficiently large amount of data to produce precise granular estimates. Therefore, using Facebook data to supplement the IPS as suggested in the article seems indeed very attractive.

Assessing the use of social media data for tourism statistics

Producing trusted statistics requires estimates of a high standard and that the use of data is ethical. In this section, we assess how social media data measures up against the criteria we use to quality assure all ONS official statistics.

Coverage and representativeness

The first questions to be asked are: Who is on social media? Who is not? How accurate a picture does the data paint of UK society?

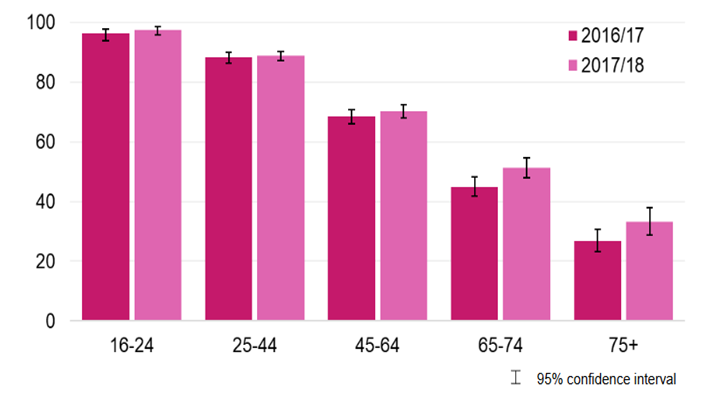

Whilst the younger populations are well represented on social media, it is not the case for all age-groups; the same observation applies to genders, ethnicities and occupations. For example, in 2018, almost all (98%) of adults aged 16-24 in England used social media, compared to only a third of those aged 75 and over (33%), as shown in Figure 1. More women said they used social media (80%) than men (74%) and people in the white ethnic group were less likely to use social media than people from the Mixed, Asian or Black ethnic groups. Of course, if our population of interest is tourists visiting the UK and migrants, we need to understand social media behaviours worldwide.

Figure 1 – Percentage of social media users by age groups in England. (Source: Taking Part Survey – Department for Culture, Media and Sports)

In 2018, the most popular social media platform in the UK is still Facebook, followed by YouTube and Twitter, however Facebook no longer dominates the social landscape worldwide. At the World Economic Forum in 2017, social media strategist Vincenzo Cosenza reported that LinkedIn and Instagram have moved into pole position in several countries in Africa, Iran and Indonesia. Platforms such as WhatsApp and Snapchat are also steadily gaining popularity. Chinese citizens have their own platforms such as WeChat, Sina Weibo, Tencent Qzone. Russian nationals prefer VK and Odnoklassniki, and studies have shown that Instagram is very popular with Arabic citizens.

It becomes clear that using only Facebook data will not capture an accurate image of tourism in the UK. One can then imagine the immense task of collecting, storing and analysing simultaneously multiple social media data sources. Data would need to be acquired from multiple platforms, and huge volumes stored securely. Whilst this is something that ONS is already doing with a wide range of data sources, and even though the data itself may be free, it is clearly not a cost-free process to understand and process the data.

There is also a bigger challenge. As most social media users likely have accounts on various social media platforms, perhaps with varying usernames, how do we avoid multiple counting? How do we account for those who are not on social media?

Accuracy and Relevance

Of all the concerns about social media data, the most publicised is probably the veracity of the data, commonly referred to as “fake news”. Can we trust what people claim to be on social media?

For example, with tourism statistics, we need to know the countries of residence, which could be extracted from users’ profiles. When investigating Flickr data, we observed anomalies such as users claiming to be “citizen of the world” or being from “Black Pudding Land”. To overcome this problem, we adopted a work-around described in a related research which consists of using geolocations of images posted over 12 months by a user to infer his/her country of residence. This method is in line with the UN definition: a person’s country of residence is where he/she has spent the most time during the previous 12 months. However, this approach raises some issues:

- First, if someone travels the world but does not post regularly on social media, we will not see his/her movements.

- Secondly, the approach relies on the users sharing their locations. However, with Twitter for example, it is estimated that only one in five tweets are geotagged.

- Thirdly, this approach requires that we download at least 12 months of historical data for a given user at the time this person enters the UK. However, in the case of Twitter, we can only download 1 month of historical data.

But more importantly, there is the issue of ethics. Is it legal and ethical to use social media data to produce official statistics?

User needs and perception – ethics

It is important here to separate the issues of legality and ethics. From the legal viewpoint, different social media companies adopt different data sharing policies. Companies such as Facebook, LinkedIn or TripAdvisor would not allow free download of their data even for research purposes, while others such as Flickr do. This is one reason why many researchers in academia use Flickr even though it is not a representative data source in terms of number of users.

But even though it is legal to use certain social media data in research, is it ethical to do so? In the context of government surveys such as the IPS, participants give informed consent, meaning they grant permission to collect their data in full knowledge of the possible usage. However, users who sign the Terms & Conditions of social media platforms and put their personal data in the public domain did not explicitly give consent for their data to be used for producing official statistics. Therefore, is it ethical to bypass their informed consent? Does the data belong to the users or the platform owners? One needs to find the right balance between user needs and ethics.

With this in mind, we undertook some investigation using Flickr for tourism statistics. We limited ourselves to downloading the metadata such as the photos’ geolocations, associated hashtags, dates when the photos were taken, photos titles and descriptions, but stayed clear from downloading personal photos. Furthermore, we only computed aggregates (e.g. statistics on tourism by countries of residence) but do not store or publish individual data.

We want to ensure that we meet agreed national ethical standards for all our work. So the research was presented to the independent National Statistician’s Data Ethics Advisory Committee (NSDEC). NSDEC was established to advise the National Statistician on the ethical appropriateness of using innovative data sources for public good. It includes representatives from both the public and the private sectors, academia, charity workers as well as members of the public to ensure that all viewpoints are taken into consideration. NSDEC members agreed that the exploratory work could proceed.

Coherence and comparability

One important characteristic of official statistics that makes it stand out from market research is their coherence and comparability over time. Indeed, as we produce a time series of quarterly tourism/migration estimates, in order to understand travel patterns, both the data source and the methodology need to be consistent over time.

Such comparability could be difficult with social media data. Indeed, it is common knowledge that social media platforms suffer significant fluctuations, losing and gaining popularity over time, sometimes disappearing and being replaced by new platforms. There is also a risk linked to mergers and acquisitions. For example, Instagram used to be freely available for research until 2012 when it was acquired by Facebook and changed its Terms and Conditions, granting itself the right to sell users’ photos to third parties without notification or compensation. This could represent a high risk for ONS time series if we were to use a data source that ceases to exist or ceases to be compliant with government policies on ethics. We need to develop a methodology that would allow us to identify and adjust for these fluctuations in order to produce robust statistics.

So, is social media data only good on paper?

Despite all the limitations discussed above, one can’t deny the huge potentials of social media data. At the top of the list are the timeliness of the data, its geographical granularity, as well as the richness of the information it carries. Surveys only provide numbers but lack the insights of social media data to help explain the why. Using long questionnaires to capture precise information adds to respondent burden, which may increase drop-out and negatively affect the survey quality.

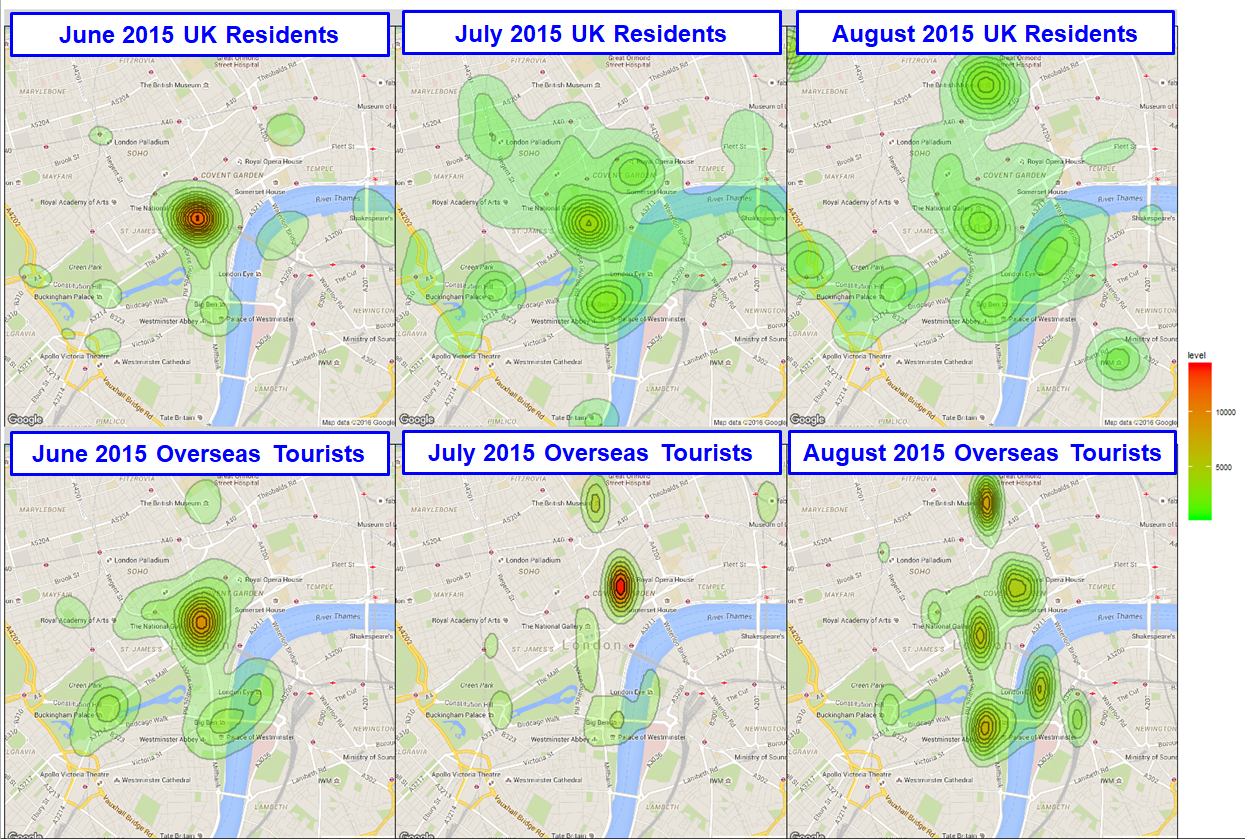

Social media data appears as the ideal data source to complement survey data and to mitigate such limitations. Because of its timeliness, it could be used as an early indicator. It can also be used to provide a snapshot of a situation down to the low level needed for small areas. An illustration of such use can be seen in our exploration, described here, which used Flickr data to compare behaviours of overseas tourists and UK residents in London.

We downloaded the geolocations of photos taken in London during the period from June to August 2015 and uploaded on Flickr. We separate, without identifying individuals, photos uploaded by UK residents and overseas tourists and produce the heatmap shown in Figure 2. We can clearly identify areas popular with tourists. The investigation could also be augmented with sentiment analyses on hashtags and photo descriptions. This shows that this approach may provide some useful analytical insights which are not possible with the survey data, despite the remaining challenges for producing robust official statistics from social media data.

However, care needs to be taken in interpreting results. Unlike surveys that are designed specifically to be fit-for-purpose, social media data is subjective by its nature and insights are often inferred from data that has not been designed to answer specific questions. More research is still needed to fully understand possible bias and to overcome it.

Figure 2 – Heatmap showing geolocations of photos uploaded on Flickr between June and August 2015 in London. We can observe differences in behaviours between UK residents and overseas tourists. Whilst UK residents’ presence seems more spread out, tourists are attracted to landmarks as we can clearly observe the hotspots. However, we need to be careful with any interpretation because the number of photos uploaded by UK residents is much larger than that of tourists. Flickr is also much less popular compared to Facebook or Instagram, for example, so this behaviour may not be representative.

Conclusion and future work

So far, our research has shown the potential for using social media data to draw analytical insights where it would be too costly or slow to collect information by surveys. At the same time, it has highlighted many challenges with using social media data to produce official statistics in general, and tourism statistics in particular. Of course, we should not close the door to using such a rich data source in the future. However, in our mission to produce trusted statistics for public good, we need to ensure that our official outputs are to the right level of quality and inform public perception of what we do. If we are to use social media data in official statistics, we need to answer the challenging questions raised in this article, and more importantly, be transparent about what we do and how we do it in order to build trust.

To this end, we work in close collaboration with academia, other government departments, as well as National Statistical Institutes worldwide to explore novel data sources and to investigate state-of-the-art data science methods. In the particular case of measuring tourism and migration, for example, we are learning from other countries that have made progress in this domain, such as the Dutch Centraal Bureau van Statistiek (Statistics Netherlands) that investigates the use of mobile phone data to estimate travel patterns across their borders. And, to ensure that our on-going research is ethical, we benchmark against the NSDEC ethical principles, and also against other standards such as the Data Science Ethical Framework published by the Government Digital Service (GDS).

ONS’ data strategy for official statistics prioritises exploring information already provided to government bodies, such as administrative data, using new data-sharing powers approved by Parliament. ONS has recently published a report on one such initiative, exploring the use of administrative data to transform population and migration statistics. Having said that, we continue to be committed to exploring the potential of novel big data sources, whilst developing methods to overcome their limitations. There are certainly challenges to be met, but it is an exciting time!

If you would like to know more about the work the Data Science Campus is doing, using data science and exploring novel data sources, please visit our project pages.

Lanthao Benedikt, Emily Tew – Data Science Campus, Office for National Statistics