How does living in a more deprived area influence rates of suicide?

Every year, organisations and communities come together on World Suicide Prevention Day to raise awareness of how we can create a society where fewer people reach the point where they feel suicide is their only option. Ben Windsor-Shellard from the ONS, along with Magdalena Tomaszewska and Mette Isaksen from Samaritans, reflect on the latest suicide figures and analysis of suicide rates by local area deprivation.

The suicide rate remains higher than earlier years

On 1st September 2020, the Office for National Statistics published 2019 statistics about suicides registered in England and Wales, showing that 5,691 people had died by suicide. Behind every statistic is an individual, a family, and a community devastated by their loss. According to the figures, the 2019 suicide rate for England and Wales was 11.0 deaths per 100,000 people, the highest seen since 2000.

Annual suicide statistics are vital for understanding the demographics of those who take their own life and can help inform decision makers and others that are working to protect those most at risk. This year the ONS and Samaritans have teamed up to look at how one key risk factor – living in a deprived area – has affected suicide rates over the past decade.

The impact of deprivation and suicide

When specifically looking at rates in England over the past decade, overall, men and women living in the most deprived areas tend to have higher suicide rates than those living in the least deprived areas.

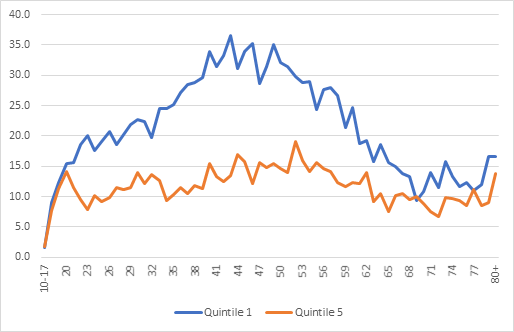

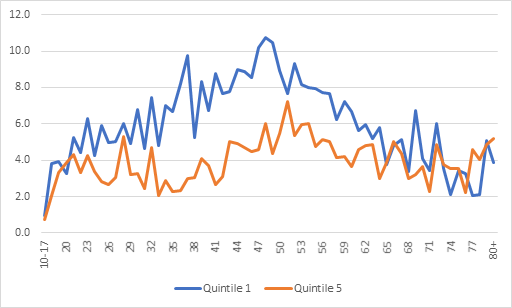

However, the gap between the most and least deprived areas is only seen among those of working age. Living in a deprived area increases suicide risk for nearly all working ages but those aged between their late 30s and late 40s were affected most. For this age group, suicide rates tended to be more than double in the most deprived areas compared to the least deprived.

Over the past decade, middle aged men in their 40s and 50s have had the highest suicide rates of any age or gender. By deprivation, middle-aged men, living in the most deprived areas, face even higher risk with suicide rates of up to 36.6 per 100,000 compared to 13.5 per 100,000 in the least deprived areas (figures for men aged 43 years). In the least deprived areas, rates among middle aged men are like those of other ages.

The gap between the most and least deprived areas was generally not seen among those aged 20 years and below, particularly in men, and in those of retirement age. For these ages, it’s likely that risk factors other than deprivation are more important. For young people, risk factors include adverse childhood experiences, stressors such as academic pressures and relationship difficulties, and recent events such as bereavement. For older people, psychiatric illness, deterioration of physical health and functioning, are known risk factors.

Figure 1: Age-specific suicide rates for males by Index of Multiple Deprivation, England, 2010 to 2019 registrations combined.

Figure 2: Age-specific suicide rates for females by Index of Multiple Deprivation, England, 2010 to 2019 registrations combined

Why are suicide rates higher in deprived areas, particularly in middle aged men?

Suicide is rarely caused by one thing. A complex mix of social, cultural, psychological and economic factors interact to increase an individual’s level of risk. But we know from research that unemployment is a key risk factor for suicidal behaviour in men along with economic uncertainty and unmanageable debt. While recent Samaritans research has also found that a lack of both social connection and purposeful employment has a particular effect on less well-off, middle-aged men’s wellbeing.

The impact of deprivation on suicide rates in Wales

The overall pattern of suicide by deprivation in Wales is similar to that in England with rates of suicide are higher in the most deprived local areas when compared to the least deprived local areas. The number of suicide deaths in Wales are too small to conduct equivalent analysis by age.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates

The impact of the pandemic, both economically and emotionally is a major concern for suicide prevention. The latest ONS figures show that there were over 700,000 fewer people on payroll during lockdown, and the most deprived local areas have been affected the most, in terms of mortality. Additionally, almost one in five adults (19.2%) were likely to be experiencing some form of depression during the COVID-19 pandemic in June 2020; almost double the number before the pandemic (July 2019 to March 2020).

The coronavirus pandemic has led to new challenges for all of us, however, a rise in suicide rates is not inevitable and we will not know whether the pandemic has affected suicide rates until the UK-wide statistics are released next year. But we do know that suicide is preventable, and that’s why it’s essential people are supported through this difficult time before they reach crisis point.

Where to go for help?

If you need to talk, you can contact Samaritans on 116 123 at any time or visit the new self-help tools on the Samaritans website.

Other sources of support include Papyrus – a national charity dedicated to the prevention of suicide among young people; The Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM) works to prevent male suicide and offers support services for any man who is struggling or in crisis; other services and support can be found on the NHS website.

Ben Windsor-Shellard, Head of Lifestyle and Risk Factors Analysis at the ONS