A global balancing act – exploring the asymmetries in world trade data

Statisticians and trade negotiators have been scratching their heads to explain a phenomenon called ‘trade asymmetries’, where different countries’ estimates of trade with each other do not match. Adrian Chesson writes about ONS’s latest work, in collaboration with our bilateral partners such as the US and the Republic of Ireland, to explain some of the differences between the UK’s trade data and those of its biggest trading partners.

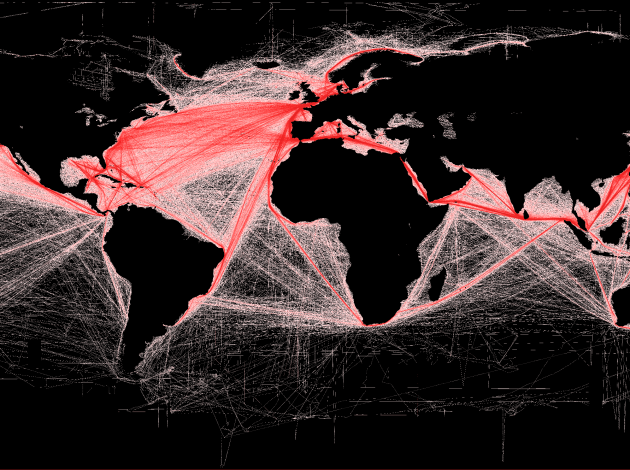

Within global trade statistics there is a known problem called ‘asymmetries’. Asymmetries are where two countries’ trade statistics will paint different pictures, sometimes allowing both to think they have a trade surplus with each other. This is a global problem. Indeed, when you add up the globe’s trade statistics, we find that the world has a trade surplus with itself of around £350 billion.

As the UK prepares to leave the European Union and seeks to negotiate its own trade deals, it has become even more crucial that we have a deeper understanding of our trading relationship with other countries.

Here at ONS we have been working hard to identify what might be leading to these asymmetries. Today, we’ve published a new article which looks in detail at our biggest trade asymmetries, particularly with the US. We’ve found that in 2016 the UK reported a trade in services surplus with the US of around £23 billion, while the US reported a trade in services surplus of around £10 billion with the UK, a difference of around £33 billion.

Collaboration

In collaboration with officials at the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, we have so far been able to identify what is causing roughly £4 billion of this £33 billion. Our analysis is ongoing and we are working to identify further causes of asymmetries.

The £4 billion difference estimated so far is down to definitions, primarily due to differing methodologies when measuring financial services, where the US is continuing its work towards implementation of the UN’s Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual Version 6 (BPM6).

In addition, the US includes Crown Dependencies (such as the Channel Islands) in its definition of the UK in its figures, but they are excluded from ours.

Sizable gap

However, there is still a sizable gap between the two sets of figures that we haven’t yet explained. It may be that different data sources and sampling variability could explain some of the differences.

There is still a lot more work to do, but our investigations are helping to explain the gap and ensure that ONS is able to produce high-quality and internationally comparable trade statistics, ensuring that our business leaders and trade negotiators have the information they need to take important decisions.

The full article looking at the UK’s trade asymmetries can be found here.

Adrian Chesson is Head of Balance of Payments and Trade Statistics for the ONS